The 2024 Indian River Lagoon Report is an annual health assessment of the Indian River Lagoon (IRL) and is the evolution of the Marine Resources Council (MRC) Report Card, first published in 2016. This year, MRC scientists gathered data from partner and government organizations to assess five Lagoon health indicators: harmful algae, seagrass coverage, sediment health, wastewater spills, and water quality.

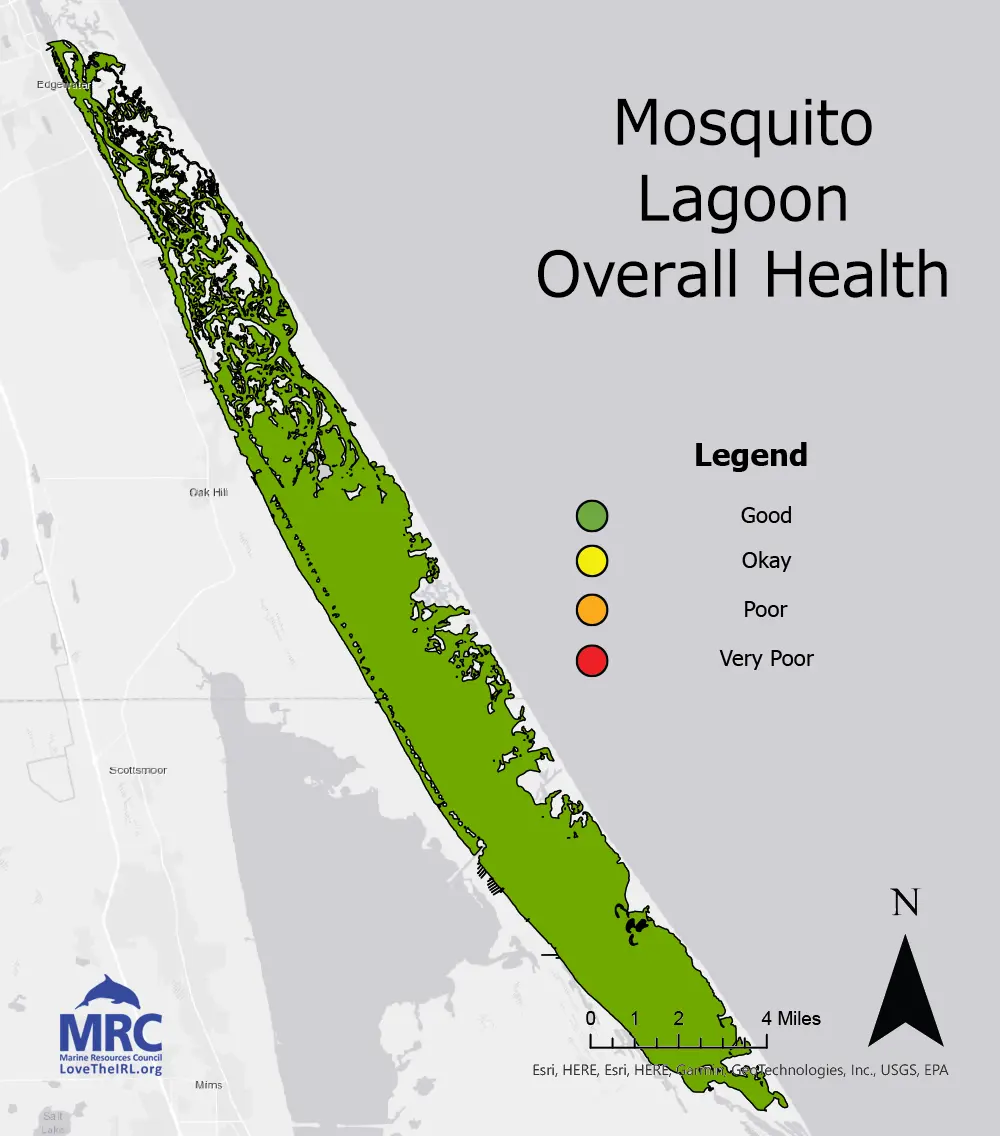

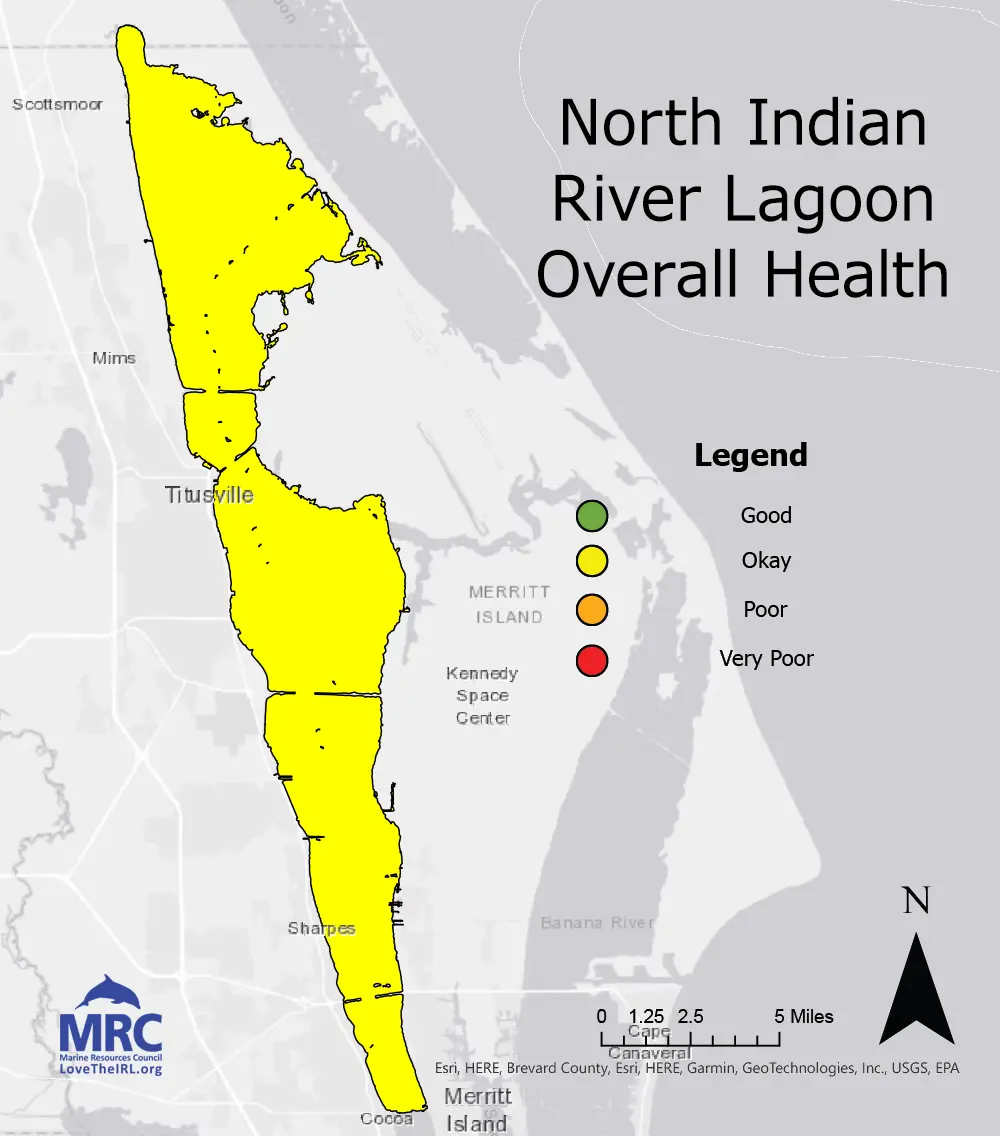

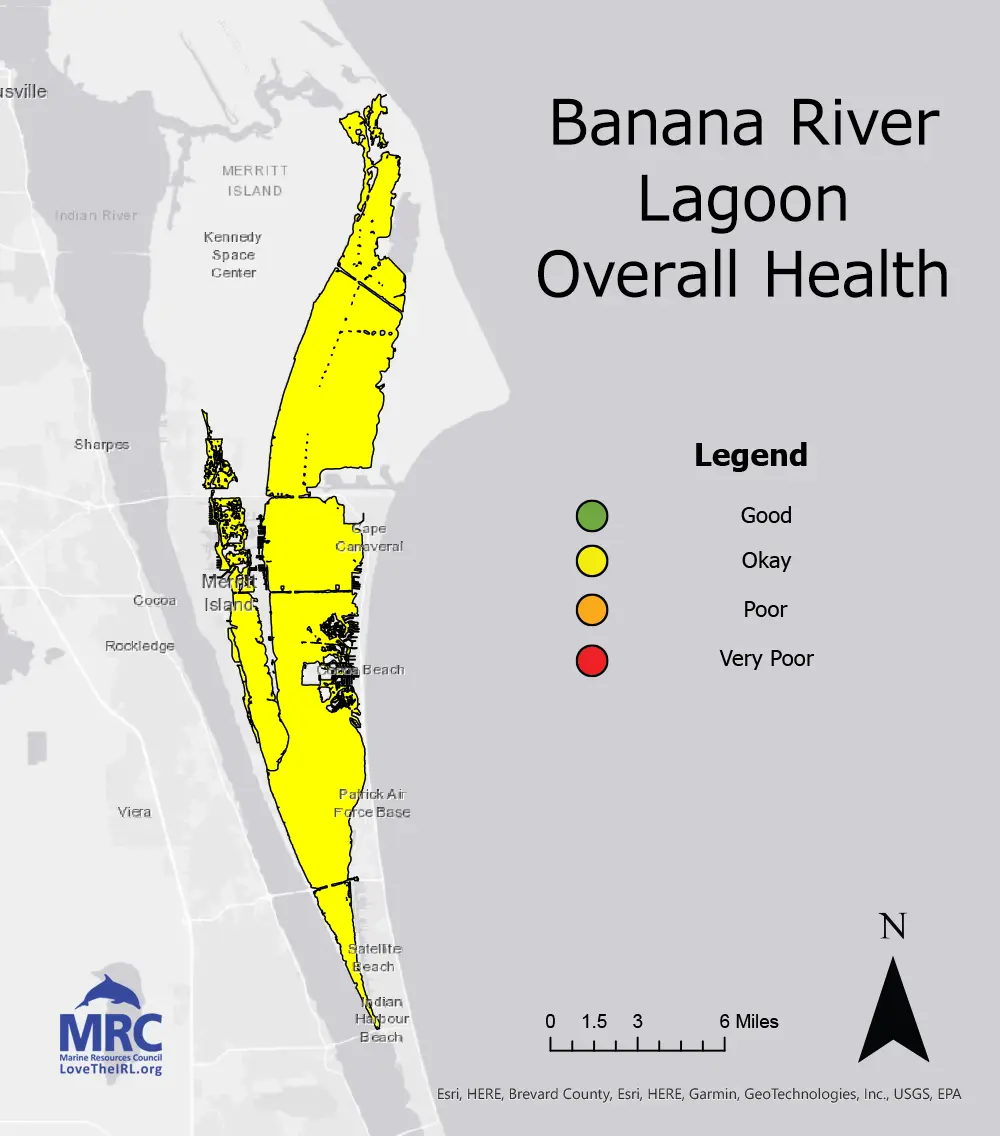

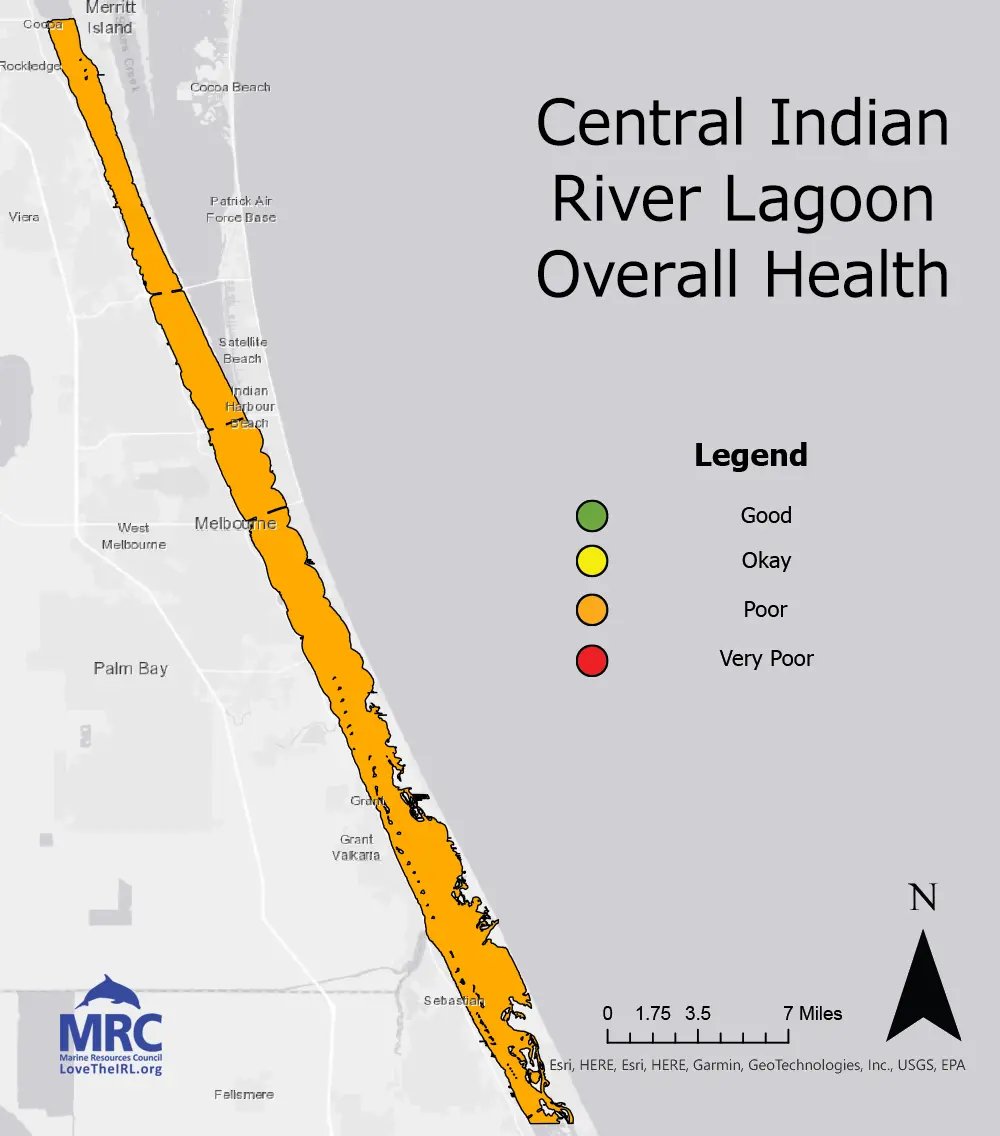

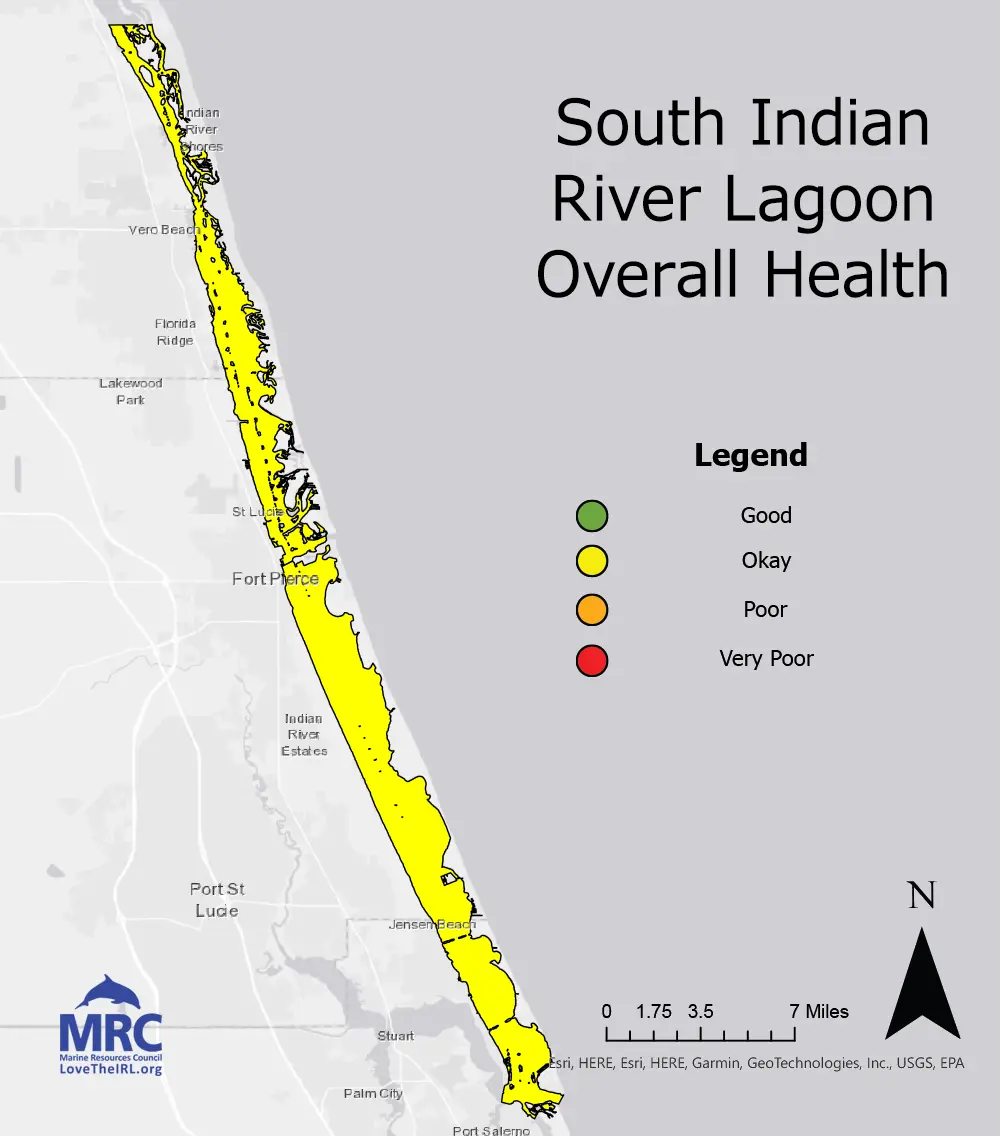

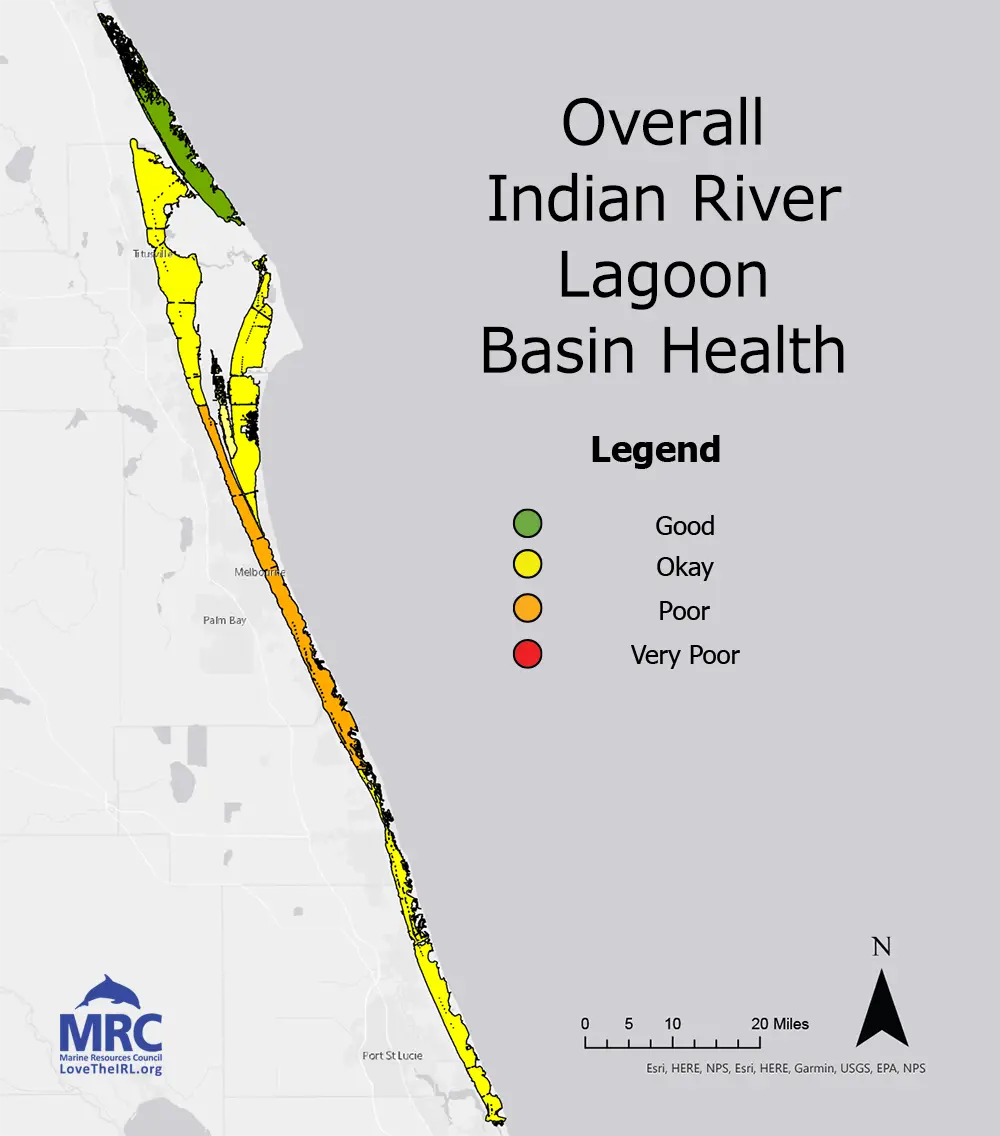

Health indicators were measured for each of the five sub-basins (north to south: Mosquito Lagoon, North Indian River Lagoon, Banana River Lagoon, Central Indian River Lagoon, and South Indian River Lagoon) on a scale from 0 (very poor) to 3 (good). The five indicators were combined for a basin-wide average and are presented below. You can also click on individual basins to get more details.

The Results Are In!

The general health of the Indian River Lagoon has improved from 2023 to 2024 in many ways! The Mosquito Lagoon had a good year with low harmful algae concentrations and increases in seagrass coverage. The Central IRL continues to struggle with water quality and seagrass growth, but the other basins held steady or had slight improvements in several habitat health indicators. This progress is a testament to the many organizations and individuals working to reduce pollution, run off, and wastewater spills in efforts to improve water and sediment quality.

However, the work is far from done.

How You Can Help

As an individual, there is much you can do to help protect and restore our Lagoon:

- Embrace Florida-friendly landscaping.

- Keep grass clippings out of stormwater.

- Stop fertilizing your lawn.

- Advocate for buffer zones around retention ponds.

- Convert from septic to sewer or upgrade your septic system.

- Champion Low Impact Development for you and your municipality.

- Practice responsible fishing and boating practices.

- Continue to support Lagoon health initiatives on the ballot (like Brevard’s Save Our Indian River Lagoon ½ cent sales tax).

- Become an MRC member!

Important Considerations

It’s important to understand that a “good” health assessment doesn’t mean that problems are solved or improvement isn’t possible. Likewise, a “poor” assessment doesn’t mean that efforts and money were wasted. We need to continue the projects and changes that we’ve started, like septic to sewer conversion, wastewater upgrades, stormwater upgrades, living shorelines, native gardens, responsible land development, and others. And we’ll need new innovations and projects to continue restoring the Lagoon to a sustainable balance.

Lagoons are variable systems by nature that change year-to-year, season-to-season, day-to-day, and region-to-region. In 2024, there were no summer discharges from Lake Okeechobee into the Lagoon, we had a relatively dry summer, and there were no direct hits by hurricanes. This helped keep harmful algae blooms low and contributed to observed improvements in seagrass and water clarity. It was a good year for Lagoon health compared to previous years, but we can’t predict next year and the work is far from done.

It’s also important to understand how science works. Science is a process, not a subject in school or a single experiment. It involves a lot of data gathering. This means that our understanding of a problem can change as we gather more and more data. Science also involves a lot of trial and error, which means there will be failures. And that’s okay–we learn a lot from them…which means that they weren’t really failures.

More About the Health Indicators

Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs)

In 2011, the Indian River Lagoon experienced the first catastrophic “super bloom” event. This event was caused by an increase of nutrients in the Lagoon resulting in a “bloom” of harmful algae. These algae physically blocked sunlight from reaching the bottom of the lagoon, killing beneficial seagrass beds. They also used up the oxygen in the water, causing fish deaths. Additional IRL “super bloom” events occurred in 2016, 2019, and 2020 leading to further loss of seagrass, fish, and manatees.

In this Report, harmful algae concentrations were measured based on chlorophyll-a content in water quality data from Florida Department of Environmental Protection Watershed Information Network. Chlorophyll-a is used in photosynthesis (how algae get their energy), so can be used to measure how much algae is in the water.

2024 was a very good year for HABs, meaning there weren’t many and chlorophyll levels remained low. As a result, there were no significant fish kills or seagrass die-offs related to HABs.

Seagrass Coverage

Seagrass was assessed by comparing 2023 seagrass coverage to 2024 coverage using data from Save Our Indian River Lagoon’s (SOIRL) Seagrass Mapping Tool and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) Seagrass Habitat map. Seagrass is essential to lagoon and estuary health because it (1) reduces erosion, (2) removes excess nutrients (that cause HABs) from water, (3) provides habitat for fish and shellfish, (4) provides food for manatees, sea turtles, and other animals, and (5) stores carbon. Water and sediment quality can affect seagrass growth, and because seagrass is easier to see, it’s used as a habitat health indicator.

You’ll notice that seagrass coverage varies greatly by region. It increased in the Mosquito Lagoon and North IRL, stayed the same in the Banana River Lagoon, was hardly present in the Central IRL, and decreased in the Southern IRL. Scientists are still trying to figure out all the factors that contribute to seagrass death, emphasizing how complex the Indian River Lagoon ecosystem is.

Sediment Health

Sediment is the sand and soil that make up the bottom of the Lagoon. When scientists assess sediment health, they don’t just look at the grains and nutrients, they also look at the animals. The tiny animals that live in and on the sediment (called benthic infauna) are the first to be affected by pollution, even before larger animals like fish, manatees, and dolphins. Scientists study benthic infauna because their diversity tells us about overall sediment health. When there’s a lot of organic matter in the sediment from pollution like wastewater, fertilizers, runoff, or dead seagrass, the number and types of benthic infauna typically decrease.

The sediment health data presented here came from research datasets collected by Smithsonian Fort Pierce Marine Station, Florida Institute of Technology, and Marine Resources Council scientists. You may notice that parts of the IRL don’t have any sediment data. That’s because studying these types of data in the Lagoon has just begun. Because sediment health data are so limited, they could not be used in the total basin assessment. And because studying benthic infauna is new in the Lagoon, we relied on organic matter content within the sediment to determine its health.

To really understand the health of the IRL, we need to gather more sediment data from all parts of the Lagoon. This information is especially important for environmental efforts, like replanting seagrass or building living shorelines, to help restore the Lagoon’s ecosystem.

Wastewater Spills

Wastewater is untreated, partially treated, or treated sewage that comes from residential and commercial sources. The wastewater data presented here represent spills or discharges into the IRL during tropical storms and hurricanes from wastewater treatment facilities, or from accidental cuts or breaks in sewer lines. There are other sources of wastewater like discharges from live-aboard boats, but those are more difficult to track. Wastewater spills presented in this Report are from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection Watershed Information Network and are limited to spills that directly affect the IRL watershed.

From August 1, 2023 to August 1, 2024 there were 168 wastewater spills into or in areas leading to the Indian River Lagoon—some affecting more than one Lagoon basin. These spills vary from 5-gallons to over 1 million gallons. Small spills are often easily contained and cleaned up quickly. Larger spills can lead to significant amounts of nutrients entering the IRL. These nutrients end up in the water and the sediment, potentially causing harmful algae blooms, seagrass death, and fish kills. Additionally, high concentrations of harmful bacteria like E. Coli can be found in the Lagoon after large wastewater discharges. This emphasizes the importance of investing in wastewater infrastructure improvements to prevent spills, especially as we encourage or require people to switch from septic to sewer systems.

Water Quality

When scientists and environmental professionals use the term “water quality”, they are referring to how clean or healthy the water is, which is determined by what’s in the water. Good water quality means the water is safe for people, other animals, and plants. Poor water quality can kill the plants and animals that live in or use the water, including making water unsafe for humans to swim in or drink.

- Temperature: Water that is too hot or too cold can hurt plants and animals.

- pH level: This measures whether the water is too acidic or too basic. Most living things need a balanced pH (between 6.0 and 8.0) to survive.

- Dissolved oxygen levels: Fish and other creatures need oxygen in the water to live. Low oxygen can harm them.

- Pollutants: Things like dangerous chemicals, nutrients (nitrogen and phosphate), trash, and bacteria can lead to poor water quality.

Here, we assessed values of pH, turbidity (which relates to water clarity), total nitrogen (high nitrogen can lead to HABs), total phosphorus (too much phosphorus can cause a reduction in dissolved oxygen levels), dissolved oxygen, and chlorophyll-a (how much algae is in the water). Salinity levels are important for Lagoon health assessment, but were not included in this analysis because they are highly variable on short time spans and across small areas. Data were gathered from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection Watershed Information Network.

Good water quality is important for maintaining healthy ecosystems and for human use, like drinking, swimming, and fishing. Poor water quality can lead to problems like algae blooms, fish kills, and the spread of diseases. Overall water quality has improved 2023 to 2024, though not evenly across the entire Lagoon.

Marine Resources Council has partnered with Surfrider Foundation Space Coast to collect bacteria data from Lagoon and tributary waters. Check out Space Coast Blue Water Task Force for bi-weekly (every two weeks) bacteria level reports.

Interested in learning more?

Click on each basin on the map above to find out more about the five health indicators for each Indian River Lagoon basin. If you want to learn more about how health indicators were assessed, check out our methods.

Thank you to partner organizations, government agencies, collaborators, and many others who provided data and guidance for the Report. We couldn’t have done it without you! Please see our full list of acknowledgements included with our methods.

Your Financial Support Makes It Happen!

Donate to become an Annual Member Today!

Marine Resources Council (MRC) coordinates Lagoon-wide efforts to Save the Indian River Lagoon, but we need your support to succeed. It will take a community to save the Lagoon, working at all levels.

MRC is holding government workshops, coordinating diverse stakeholder groups, showcasing community leaders, and working with businesses and individuals to encourage actions that will help save the Indian River Lagoon.

This website is managed by the Marine Resources Council, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that has been dedicated to protecting and restoring the Indian River Lagoon since 1983.

Marine Resources Council • 3275 Dixie Hwy NE, Palm Bay, FL 32905.

Site development by Editype.